My search for the first snowman

I was in constant contact with a dream team of experts

Who made the first snowman? Who first came up with the idea of placing one snowball atop another and sticking a carrot in the top sphere? This was my quest for over six years. It would deplete my bank account, test my marriage and get me in with a lot of cool celebrities.

I was at a career crossroads of sorts when I decided to tackle this project. Weary and jaded from working as a writer and illustrator in the shrinking magazine field for over 15 years, my flashier assignments were well behind me. I was looking for something that would provide purpose. Something to wrap my brain around. I was a huge Sherlock Holmes fan although the idea of solving a crime didn’t interest me. No, not just any mystery but one of life’s great mysteries, along the li

nes of who made the first sandwich…or who told the first joke. My subject needed to be famous yet unknown. Beloved but mysterious. Then I thought of Tim Burton’s Batman. It intrigued me how he took such a white-bread character (the campy Adam West version) and cast, of all people, Michael Keaton, to make a very dark, serious character study. Burton had successfully turned the icon on its head. Could I do that with the snowman? So began my wild goose chase.

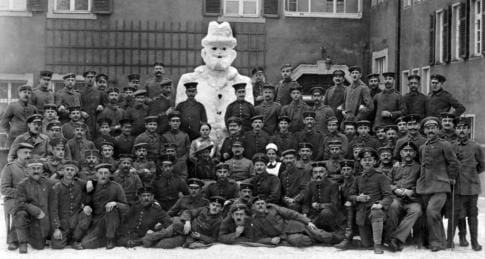

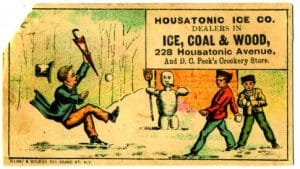

I started in the more obvious places, places I would consider the archaeological digs of kitsch snowmen long discarded; the flea markets and eBay. But as I suspected, these artifacts were of the modern snowman, the results of folk-art gone bad and while it resulted in a pretty cool (and enormous) snowman collection, I had no real clues to the snowman’s past. Books on winter pastimes were vague on the subject and wrongly concluded when snowman-making become popular. Instead I enlisted the help of leading historians from around the world who seemed genuinely excited to take a break from whatever it was they were working on and be invited on my own personal Holy Grail. Now I was taking it up a notch, scouring museums and libraries in the oldest cities, examining their public and private art collections, gaining access to archived journals (which meant putting on the payroll Columbia history students who knew Dutch and Old English to translate leads in old diaries and chronicles I suspected mentioned snowmen or contained snowman-like activities.)

Two things became clear early on; 1) This could not have been accomplished sooner. It took the maturation of the Internet. Using Jstor, the world’s journal database, I had access to absurd university papers from nearly every institute. Plus, my inbox was a who’s who of superstar historians and professors. I had the famous archaeologist, Dr. Nigel Spivey, art theorist Matt Glatton, the distinguished Arctic studies Prof. Dale Guthrie, and many others…all working on Project Snowman. I was in constant contact with a dream team of experts who were text messaging me clues from their areas of expertise from all cold corners of the world as I pieced together the birth of the snowman puzzle. 2) I realized I really stepped into it. I found a subject no one had thoroughly researched before, chock-full of secrets no one had yet published. It was like I found a winning lottery ticket.

Speed ahead four years. Like that pivotal moment in the movie Castaway when we see these words appear on the screen and cut back to see a buff Tom Hanks now a seasoned desert island virtuoso, I too was now a different person. Possibly

even more snowman shaped. But definitely a gentleman scholar and confidant I have become the leading authority on the subject of the snowman. I had divided my findings into logical, sequential chapters. Initially, my editors fought my plan to have the book going back in time (history books are always in chorological order) but I wanted my book to unfold as a mystery with the solution appearing at the end. The chapter titles were to include The White Trash Years, The Hollywood Years:

“There’s No Business Like Snow Business,” The Dean Martin Years: Drunken Debauchery and Other Misgivings, The Era of Snowman Deconstructionism, Belgian Expressionism and Early Classism in Snow Sculpture. These were punctuated by benchmarks for this frozen Forrest Gump such as The Revolution of 1870, The Snow Angel of 1856, The Massacre of 1690 and The Two Ball Theory. But of course all of this culminates to solving the true mystery, The First Snowman.

Prior to turning in my manuscript I would have to meet face-to-face with the renown Professor Herman Pleij. I needed his blessing before I went to press with my shocking tale as to the first documented snowman, a story that would upset many and put me immediately under attack. My journey to the University of Amsterdam would take up what was left of the winter and began by flying to Belgium and then a trolley to the Brussels city museum, where old maps charted the path politically charged snowmen made throughout the town in The Miracle of 1511. This I knew through Professor Pleij in his amazing but unknown Dutch book, De sneeuwpoppen van 1511. Detours included a visit to Arras, France, the site of a spectacular winter festival in 1434. Visiting this town I find no evidence that the town symbol was once the rat. Bruges was another stop. I went to towns in England and Germany. Art museums never brought me over to their snowmen (or schneemann) but sometimes, just sometimes, I was able to point out how they were wrong and find snowmen right under their noses.

Weeks later, an express train took me to The Royal Library at The Hague, where I met with experts to discuss the particulars of the first printed snowman which was in their possession in that historic, illuminated manuscript. The Royal Library’s collection of images of all kinds is the world’s largest at eight million+. Here I would stay until I finished combing the catalog and double-checking the results of the art experts who helped me the past four years looking for the earliest depictions of snowmen (or snowballs…or snowball fights—where there’s smoke….) I focused on the approximately 15,000 woodcuts, drawings, etchings, and paintings created before 1750 that were categorized as winterscapes, examining each suspicious mound of snow with a magnifying glass, hoping to spot anything that resembled a snowman. When I finished that arduous task a week later, I hitched a ride to Amsterdam from an old friend who also acted as my Dutch translator. Always looking for any snowman references, we spotted a very old mural of Willem Barentz on the outskirts of the city. I had heard about this 200-year old wall portrait and made a point of making a detour down the street named after the important explorer. Barentz died trying to find the Northeast Passage to China and engravings in the sixteenth century atlas Petits Voyages by the famous de Bry brothers depicted snowmen in the distance. Did Barentz discover the first snowmen in Spitsbergen or was this artistic license? (That riddle was resolved a year ago and no longer part of the bigger picture.) Once inside the city, I made my way to the university by foot. Our route took us past some of the city’s most popular tourist attractions: a quick peek was all that was needed in “The World’s Smallest Art Gallery” (the size of a closet)…a brisk walk past its famed Banana Bar flanked by bikers offering coupons…and a hurried tour in Rembrandt’s house, where the great painter went bankrupt, only a snowball’s throw from the center of the city.

Finally, I arrived for my long awaited appointment with Professor Pleij or as his code name in the mission, The Big P. As the leading authority in medieval cultural studies and, more importantly, snowmen in the Middle Ages, our lengthy conversation regarding my fieldwork and conclusions was crucial.

My meeting with the distinguished Professor Pleij ended with him congratulating me for what he considered a sufficient feat and gave me his blessing. My Dutch friend documented the moment and our good-bye handshake with a digital camera and then looking at his coupon asked if I remembered where we passed the Banana Bar.

Bob Eckstein is author of the non-fiction book, The History of the Snowman and his cartoons now appear in The New Yorker, New York Times, Harvard Business Review, Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, Reader’s Digest as well as many others. He has been a regular humorist and award-winning illustrator for over thirty years, appearing in publications like The Village Voice, Spy, Time Out New York, National Lampoon, Details, GQ, Playboy, Newsday, and Sports Illustrated. Bob is currently working on a movie based on his History of the Snowman book, and publishes the popular online magazine Today’s Snowman. http://www.historyofthesnowman.com/

This article was included in the December 2009 issue of PlanetChristmas Magazine.

By Bob Eckstein